A recently published paper about an acute fuel shortage and trade relations with Venezuela summarised Cuban official government statistics as a story of discontinuities, puzzles and obfuscation. Similar words have previously been used by economists to describe Cuban national accounts. They are arguably also an accurate summary of life in Cuba more broadly.

As the Spanish edition of Russia Today broadcasts the latest breaking world news in September 2022, including major stories about a grand conspiracy to pay workers of the US Postal Service less than they rightfully deserve, righteous industrial action by employees of other US delivery services, corrupt foreign politicians and, yes, we’ve all been waiting for it, the final end of the global hegemony of the US Dollar, mentioning in passing a minor and obscure armed conflict in Ukraine, I try to make sense of daily life in Havana. Mainly, I would keep running around in circles, fail miserably at getting even basic things done and understand next to nothing about how Cuba might function. It is no easier to know where to start with recounting the experience. Of course, my observations during a short stay on the largest of the major Antilles are made at particularly difficult times: post-Covid lack of tourism and foreign currency, galloping inflation, lasting crisis in Venezuela and fuel shortages, worst economic downturn since the collapse of the Soviet Union, what else? They are probably not representative of a more general state of affairs nor could they in any way do justice to the complexity of this beautiful island nation. In no particular order, therefore, below a number of striking observations.

Arrival in Havana

Waiting

Patience may very well be the most outstanding quality of the Cuban people. Those who think that the Brits are good at standing in line would do good in thinking again. Waiting for food rations, waiting for electricity to be turned on again, waiting for a clerk to appear at a counter, waiting for buses or trains, waiting to be put on waiting lists, waiting for political or economic reform, waiting since 1962 for the US to lift their embargo. The list goes on. Even waiting without knowing what one is waiting for does little to push Cubans to the edge, assuming that the concept of an edge isn’t entirely nonsensical in the realm of Cuban patience in the first place. My own initiation to Cuban waiting occurs at 8am on a Sunday at José Marti International Airport. As one of the first passengers to disembark a Mexican budget flight, I am also among the first in line at immigration, where an official glances at my passport, puts it aside and instructs me to step back and wait behind a red line, with no indication whatsoever about what to wait for. It would be a lie to claim that it is not with some anxiety that I spend the next hour watching all other passengers passing immigration and my passport being handed around hesitantly between a series of border officials before it disappears behind the door of a random office. I wait for a few hours more before being questioned sequentially by several immigration and customs officials about the nature of my visit to Cuba, all of whom find it hard to believe that tourism is the only purpose. I make it to La Havana Vieja by mid-afternoon.

The truly impressive aspect of the Cuban waiting game, however, is the discipline with which it is played in settings where interpersonal relationships are of a less authoritarian nature than in dealings with police, immigration or customs officers. Etiquette requires that the last person to present themselves at the provider of the good or service that is the subject of the wait pinpoint, through clearly audible inquiry among all others present, the last person in line, who will identify themselves by raising a hand. As soon as the penultimate arrival has been identified and the order among the preceding and succeeding waiter has been established, one can calmly wander off for a nap in the shade or to take care of any other business. Although helpful, it is not even necessary to remember the person ahead in the line not to miss one’s turn: fellow waiters will not fail to actively look for and remind the waiter whose turn has come. My introduction to this practice, later on the same Sunday when getting in line at a Havana bank to withdraw cash, is somewhat disconcerting as my shy questions about what people were waiting for are met with abrasive berating by several waiters for not properly yelling, “quién es el último?” As a resident of France, where the cutting of waiting lines and the gaming of various rules and systems of public administration are no less than national passions, the experience is truly astonishing.

Waiting for…

Cuban Spanish

Language can be a barrier to an in-depth understanding Cuba that is not to be underestimated for a traveller like myself, whose command of Spanish is far from flawless but seems perfectly adequate in Mexico and most Central American countries. Of course, Cubans speak Spanish. But not only does the number of words people can utter per second increase by a factor of two to four as one enters the country from Mexico, but this increase in speed also comes at a significant expense phonetic redundancy. Non-essential consonants at the end of words are consistently omitted. The pronouncing any of the last two to five letters in words, or indeed many of the consonants in any word, seems optional and vowels barely seem to require opening one’s mouth. Combined with a striking absence of Latin American politeness, and the “permisos” replaced with “muévete”, “vamos” or a rhetorical “pero qué estas haciendo?”, communication takes some time to get used to.

Opening hours

A challenge Cubans and visitors face in going about daily life and running errands, or waiting for the right time to run them, is related to not knowing when (or indeed if) shops, offices or other places of interest are open. It’s hard to generalise but it appears that the only rule related to this topic is that de-facto opening hours never coincide with those displayed and are, generally, significantly shorter. Allow me to illustrate by way of examples.

Offices of Etecsa, the national telecommunications firm, generally display opening hours from 8am to 5pm. On any given day, however, doors tend to be closed at 9am because someone didn’t make it to work, at 11am because someone already called it a day, or at 3pm because a break takes longer than anticipated. The same applies to any other service. Also, the above illustrative reasons for spontaneous closure are usually not obvious but seem to be picked at random from a number of plausible reasons, when asked, by people present in the vicinity of the closed facility. Sick leaves, electricity outages or computers not working are of course in a category of closing reasons of their own.

To make matters worse, closing time always seems to approach much faster than opening time. After having spent a morning waiting at the Havana central bus terminal for a clerk to appear at the ticket sales office and then waiting for my turn to ask whether tickets are available, a look at the clock – it is 1pm – seems to suggest that the afternoon could be spent with a visit to the adjacent national library. The entrance is open, five staff are present in the lobby and busy staring at walls, one of whom kindly offers information. There are three ways to enter the library: 1. by being Cuban; 2. as part of a guided tour for non-Cuban visitors, for which booking an appointment upfront by phone is imperative and cannot be arranged on site; and, 3. As a lonesome visitor for consulting literature, which requires an advance appointment, one’s passport, and requesting a special permit, none of which can be arranged just before, that is 4 hours, before closing time. I admire the national library from the outside.

High-profile closures from temporary to possibly eternal: the National Library, Havana train station and the National Capitol

More prolonged closures are usually ascribed to repair or renovation works, which can last from anywhere between several weeks to eternity. Such repairs tend to affect, at any given time, an estimated 80% of buildings home to public administration or transportation, services and general points of interest. Even more astonishing, neither construction sites nor construction works are visually apparent amid all these renovations. Exhibit 1: The national Capitol, a replica of the Washington DC version, sporting gold plated roofs and arguably the only building in all Havana with not a brick out of place – closed for renovation, from August 15th to September 2nd, which is of course why it is not open to visitors on September 21st. 2. Havana Central Train Station – closed for renovation since time immemorial, judging by the accumulated layer of dust at least for the past 3 to 5 years; reopening date unknown, if ever, probably in the very distant future since no construction work appears to be underway. 3. Historic Palacio de los Capitanes Generales – all but the ground floor closed for renovation. 4. Museum of the Cuban Revolution – closed for renovation, closing and opening dates unknown. The list could be continued indefinitely.

Cars

Cuba has never been home to a thriving automotive industry. Together with the US trade embargo and a lack of resources to buy new vehicles from other foreign manufacturers, this fact has turned the island into a vintage car museum. Dodge, Cadillac, Chevrolet, Lada, Gaz, Polski Fiat, etc. etc. All makes, models and colours built in the US before the late 1950s or in the Soviet Union and its satellites between the 1960s to 1980s populate the streets of Havana and beyond, many of which in surprisingly good shape. For all their aesthetic appeal, those decades were not known for fuel efficient engines. Despite the fuel shortage of 2022, a constant scent of gasoline permeates Havana air and the taste of anything from coffee to fruit and vegetables bought at street markets.

Inflation and exchange rates

Until recently, Cuba operated a dual currency system, whereby small local transactions were made in Cuban Pesos and transactions involving larger sums or foreign goods or service in so-called Convertible Cuban Pesos. Dual currencies had been introduced in the early 2000s to reign in the use of US Dollars but remained largely incomprehensible to anyone without a PhD in monetary policy. Apparently decades in the planning, that system was abolished in January 2021, leaving a single Peso Cubano as only legal tender for all transactions. Inflicting much economic pain on the population, the Peso devalued rapidly in since 2021, both in terms of domestic purchasing power and on foreign exchange markets. And rapidly really means rapidly: depending on who you ask, inflation is estimated at anywhere between 30% and 300% for 2022. While the exchange rate published by the Cuban Central Bank, substantially unchanged since the beginning of 2022, advertises 25 Pesos per Euro, commercial banks buy Euros for 120 Pesos in September 2022 and hawkers in the street for 140 early September, up to 170 and 180 by mid-month. So, really, the dual currency system was swapped for a dual or multiple currency system, whereby Cuban Pesos buy local goods and services for as long as they are still worth the paper printed on and Euros or US Dollars, or other hard foreign currency, would buy anything else that hasn’t run out yet. Keeping foreign currency is also the only way for Cubans to protect themselves from the Peso’s rapid devaluation. Traveling from Mexico, I learn the hard way that Mexican Pesos are significantly less popular than bills signed by the chiefs of the ECB or the Federal Reserve and that not carrying a bag full of such bills makes traveling Cuba a great deal harder.

Rum and cigars

With tourism off the list since the Covid-19 pandemic and significantly fewer medical doctors sent to Venezuela in exchange for oil, the mainstay and indeed pride of the Cuban export economy are rum and cigars. Both products are produced in pre-industrial and manual processes, largely unchanged since the 1950s.

Visitors can learn about the glorious history of sugar cane, introduced to Cuba by Christopher Columbus in 1493 and harvested for centuries using slave labour, at the Havana Club Museum. The process of distilling and refining rum is strictly supervised by Los Maestros, a title requiring a qualification as a chemical engineer and at least 25 years of experience. Unrelated to rum, the Havana Club museum also prides itself of being home to Cuba’s only domestically engineered trains and functioning railway network. They are part of a 1:20 scale model of a sugar plant.

Havana Club

Cigars are rolled manually at a number of state-owned plants in Havana and at tobacco farms across the island. State owned plants receive 90% of every farms’ annual harvest while farmers are permitted to retain the remaining 10% for their own consumption and sale to visitors. The manual production process is fondly referred to as massaging, not rolling, and as I learn at a farmer, más masaje se da, más guapa se pone.

Tobacco and cigars

Relative prices

Cuba is one of the very few remaining nations of the world that operate a predominantly planned economy. Although the relative size of the public sector has decreased in recent years, the state still accounts for most of output and more than 70% of employment. Prices are set by the Ministerio de Finanzas and Precios, housed in a sympathetic-looking, Soviet-style high rise building misplaced right in the middle of La Havana Vieja. Or so the story goes. But some demand and supply mechanisms are probably also at work and who actually adheres to the centrally set prices, how pricing rules are enforced and what happens when they aren’t followed is much less clear. This seems to lead to some rather surprising price ratios between commonly purchased goods and services. Below some striking examples.

- Ferry ride across Havana Bay: 2 Pesos Cubanos.

- Guagua (sorry, bus) ride across central Havana: Whatever bill upward of 20 you hand the driver. I hand over a bill of 50 and get some token change after asking for the third time and looking mean.

- Taxi ride: 8 Pesos per kilometre in central Havana, according to the Ministerio de Precios in September 2022. I hail a ride at Parque de la Fraternidad to get to the central bus terminal near Plaza de la Revolución, some 4.5km away. Asking price: 1,500 pesos, lowered to 700 after brief negotiation. I offer 400, am told that 700 is the regulated price and instructed not to pester drivers any further with a dismissive suggestions that I better be walking. I walk.

- Litre of gasoline: 30 Pesos, if the gas station hasn’t run out. That’s a big IF (see “Shortages” below).

- Mojito at La Bodeguita del Medio (where Ernest Hemingway, world renowned author, apparently drank his daily mojito): 200 Pesos.

- Mojito at La Floridita (where Ernest Hemmingway, world renowned alcoholic, apparently drank his daily Daiquiri): 400 Pesos or 10 US Dollars or 10 Euros, worth a multiple (see inflation and exchange rates above).

- Bottle of 3 year-old Havana Club rum: anywhere from 300 to 2,000 pesos.

- Bottle of drinking water: around the lower bound of prices of the bottle of rum above.

- Meal at mid-range restaurant: 1,500.

- Median blue-collar wage: 3,800 per month.

- Median salary of a university professor: 5,500 per month.

The Ministry of Prices

Shortages

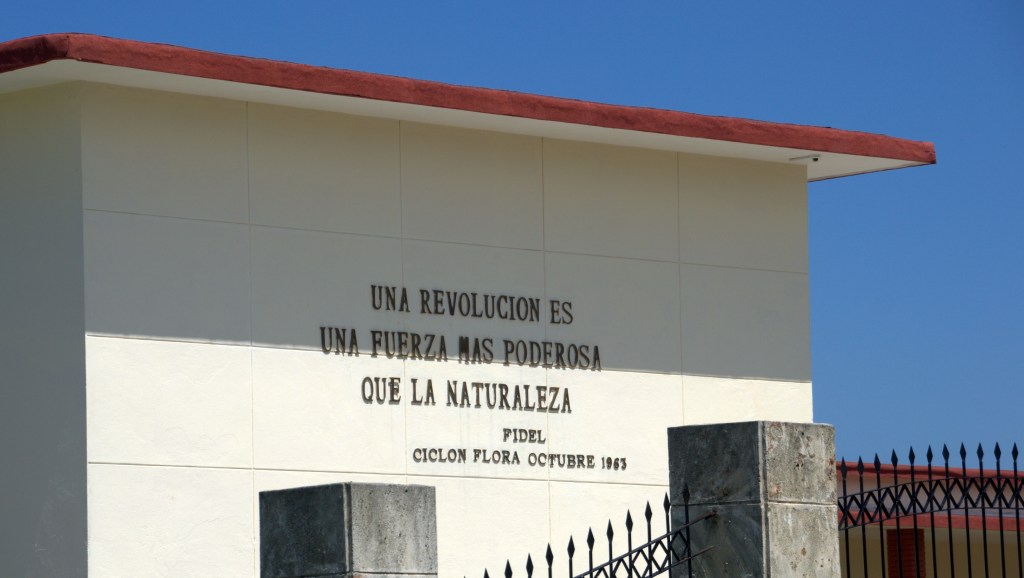

Probably not unrelated to the issue of relative prices, exchange rates, and all the rest of it, the issue of which goods and services are available when and to whom is a thorny one in 2022 Cuba. In general, there seems to be a shortage of almost everything. That is everything except rum, avocados because they happen to be in season, rocking chairs (presumably to make waiting less burdensome), Che Guevara portraits, monuments attesting heroic defeats of US and other imperialist invaders, and slogans about revolution, solidarity and fairness. Then again, many things, including those in short supply, can be bought by those who carry foreign currency.

For most Cubans, basic foodstuffs are rationed an available at heavily subsidised prices from local bodegas. The wait to be served can be endless. For those who can afford, not many given the median wage indicated above, food can also be bought from corner shops, super markets that only accept card payments in Euros and US Dollars and restaurants. A few examples of luxury shortages: “La pura” Michelada with salt and lime at La Vitrola bar in Havana Vieja comes without beer. El Café, a hip coffee shop in Havana Vieja that serves breakfast, has no bread, and neither do most corner shops in Havana that all display a sign on 2 of 3 days saying “No Hay Pan“. A serious shortage affecting most Cubans, who live on a fertile island surrounded by warm seas with ample fish stocks that nevertheless has to import 60% of its food : foreign currency, mainly earned from tourism before the Covid-19 pandemic.

A tale of abundance and shortage

Many of the 2022 shortages also seem to be at least indirectly related to the other mother of shortages, that of fuel. It is impossible to find any reliable information about its extent, root causes or government remedial policies, if any. But judging from the lines at gas stations, the taxis and buses that aren’t running and the daily power cuts in a country where electricity is mainly produced by diesel-powered generators dating back to the 1950s, it is apparent that there isn’t enough. There is some connection with the lasting crises in Venezuela, which previously provided oil at sub-market rates in exchange for Cuban health professionals. Venezuelan imports apparently halved between 2020 and 2022.

Transport, public and otherwise

I make the rookie mistake of thinking that I could catch a train out of Havana to vist other parts of the island. Havana Central Station is closed for renovation (see above). Upon inquiry, I learn from Fidel, the caretaker of my rental apartment in Havana Vieja, that trains meanwhile run from La Cubre station, behind the cargo terminal that is closed for renovation. My visit to La Cubre the next morning helps me understand that what Fidel really means is that I could spend days waiting for a clerk to put me on a waiting list for the ticket counter, and then wait for days for a train that in all likelihood does not run from La Cubre.

Public (non-) transportation

Mistake acknowledged, I enquire further with several people. Other options for getting out of Havana include, I am told, bus services for visitors operated by some of the major Havana hotels that aren’t closed and barricaded since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, which, however, hotel staff have never heard of; collective taxis that require finding, somewhere in Havana, fellow passengers that would like to travel to the same destination at the same time and a gas station that provides gasoline (see section on Shortages); private taxis that would also require gasoline, and cost multiples of an average Cuban monthly salary and of my own cash reserves; any kind of vehicle, including buses and trucks, that can be stopped along roads and whose driver agrees to carry passengers, in violation of the prohibition for foreigners to use such services; rental cars, which require gasoline, and are possibly available with reservations made weeks to months in advance; and buses by Viazul, the state-run bus service for tourists and other foreign visitors. I conclude that my highest chances of success are with the latter. Viazul also operates a webpage, which has information about schedules and an online ticketing services that is, as anyone might guess, down for maintenance. A few days later, I abandon efforts to negotiate the price of a taxi ride (see Relative Prices), walk across town to the central bus terminal, and spend the morning waiting for ticket clerks at Viazul offices. Not without pride, I leave the terminal with at ticket for an 8am bus to Viñales later in the week, after being instructed to report to the check-in counter at least 3 hours in advance on the day of departure.

El Son, Salsa, Dancing and Music

Lest I forget, another item there is oddly no shortage of are completely oversized bluetooth speakers. To the dismay of most non-Latin visitors, reggeton and other popular genres of Puerto Rican and, more broadly, Latin American pop music blast around the clock in all corners of the island. Not even the daily power outages offer a period of respite thanks to oversized batteries that power oversized speakers. For my own part, I try to avoid as many establishments and public places that play reggeton at the cost of being perceived as anti-social and take salsa classes with friendly Yalena, at El Barrio dancing school in La Havana Vieja. The music genre known today as salsa has been heavily influenced by the more traditional Son Cubano, the “Cuban Sound”, which originated on the island as a mixture of Spanish and African music (see here). I am El Barrio’s only customer and learn that, if they come, only tourists take dancing classes because Cubans have the dance moves in their blood. I also find out, days into the classes, that the adverts for El Barrio in my Havana rental apartment, the friendly support by Fidel to book classes and Fidel’s repeated presence at the dancing school were no coincidence. Yalena is Fidel’s wife.

El son

Inequality, Healthcare and Education

A striking feature of Cuba that the government never fails to point out, in particular when compared to neighbouring countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, is that there appears to be little economic and social inequality. No shanty towns, no barbed wire fences or gated communities to protect the rich, no guns, no violent crime. Although one suspects that a wealthy and politically well-connected elite must be hiding somewhere, on the face of it, most people seem to live in similarly modest material circumstances and most buldings in Havana, including grand mansions in chic pre-revolution neighbourhoods, have been turned into collective housing.

Cuba is also the only Latin American, or really the only nation on the entire American continent, that prides itself in having universal public health care and a public education system. Despite all its economic woes, education and health care remain government priorities, Cubans are highly educated and Cuba scores higher than most Latin American nations in terms of the Human Development Index. Medical education is said to be world-class and, besides rum and cigares, graduates are proudly exported to the entire world.

Probably not unrelated to collective housing, Havana also seems to be in a constant state of disrepair. The only three categories of buildings that are not on the brink of collapse are historic monuments renovated with donor funding, health clinics and schools. Add to that Fidel Castro’s villa in formerly chic Miramar and the National Capitol, construction and maintenance of which in all likelihood consume 80% of the national infrastructure budget.

Clinics and schools

Rules

Another likely reason for the striking absence of crime is that Cuba effectively remains a police state. While passing a prison, a friendly driver of a 1950s US convertible explains to me that its easy to spend a night for free at the island’s penitentiary institutions, while living life among 10 million police officers, agents and informants among in a population of 11 million. It is clear from slogans about solidarity on billboards, the signs decrying “anti-social” behaviours and instructions given by police officers and other Cubans with administrative powers vested in them that trespassing against rules and regulations is not taken lightly.

Travel to the US

The sad truth is that nearly every Cuban one interacts with as a visitor has a close friend or relative who fled, or finds themselves in the process of fleeing, the island to the US, either in a perilous crossing of the Gulf of Mexico or at the hands of traffickers through Central America and Mexico. For non-Cuban nationals, realities are not as dire. That doesn’t mean that traveling to the US is easy. For US nationals, private travel to Cuba has been premitted for one of thirteen reasons since recently, inclding to support the Cuban people and for religious activities.

Nationals of other countries can travel to and from Cuba as they please. As I find out after a conversation with a friendly group of Italian tourists at La Floridita, hours of internet research and a call to the Austrian embassy in Havana, they cannot, however, travel to the US after a visit to Cuba without applying for a visa. Owing to their economic prowess, massive reserves in foreign currency (see above) and general malignancy, Cubans are, thanks to the eternal wisdom of ex-president Donald J. T., back among the state sponsors of terrorism. The other countries labelled as such by the US government are Iran, Syria and friendly North Korea. The main implication for non-US nationals is a requirement to apply for a visa for any trip to the US and the invalidation of visa waiver authorisations, a rule enforced by the US Department of Homeland Security since August 2022. Handily, the massive US embassy in Havana, second only in size and opulence to the Russian Embassy in Miramar, issues no visas. Consular services for Cuba are handled by the US Embassy in Guyana, separated from Cuban shores by a mere 2,000 or so kilometres of Caribbean Sea.

I decide not to travel to Guayana or back to Mexcio in hopes of obtaining a US visa, and cancel without refund my flight to New York City, my outrageously overpriced Brooklyn AirBnB and the return flight from NYC to Europe. Instead, after several failed attempts to secure a ride, I now take full advantage of being the proud owner of a Viazul bus ticket and thus leave Havana bound for Viñales and in search for an alternative route off the island. I also add the US to my personal travel blacklist in the hopes that I will be better prepared one day for a return to Cuba.

Leave a comment