There are many layers that make the city of Napoli. Some are rather apparent and delineated, the presence and boudaries of others more subtle. It is not always entirely clear across which dimensions these layers cut but they certainly stratify time, architecture and culture, as well as probably a number of other dimensions, depening not least on the eye of the beholder.

To any new arrival, the most obvious layer is that of el D10S Diego. It is also the most recent layer or, indeed, the present. In its history since 1926, SSC Napoli won the Italian Serie A football championship twice, the first time in the season of 1986/87 and the second and last time in 1989/90. It was probably no coincidence that both victories, the significance of which to the Neapolitan population can hardly be overstated, occured while a certain Diego Armando Maradona was the captain of the team. Neapolitan time may well have stopped then. No other player would ever wear the number 10 jersey since the early 1990s. The stadium was renamed to bear Maradona’s name. El D10S seems to have never left the city, and lives on in the form of statues, stickers, murals, plays and other forms of popular culture and, yes, tatoos of grown men and women.

El D10S Diego never left

Beyond Diego himself, the present layer also features a number of aspects that are hard to do justice to in this short account. Narrow streets, a wide variety of architecture, inviting terraces, a breathtakingly beautiful coast line and the Mediterranean Sea. Take your pick and slice these layers according to your liking…

The diverse present layer

Then, there is the undisputable culinary layer, which gives Napoli another unique identity. A sheer endless selection of restaurants and eateries line the streets of the city and adjacent towns. Spaghetti alle vongole, insalata caprese, pastiera, pasta e patate, timballo, gnocchi alla sorrentina and, lest we forget, pizza napoletana. This list could be continued for pages before even getting to the sfogliatella and babà, along the other pastries and desserts. Located on volcanic slopes that make for exceptionally fertile agricultural land, the quality of the ingredients produced in the city’s vicinity make these Neapolitan favorites as delicious as they are simple. The only surprise, given their content in white wheat flour and other sources starch and/or sugar, is that overweight does not (yet) appear to be a major problem in Napoli.

The culinary layer

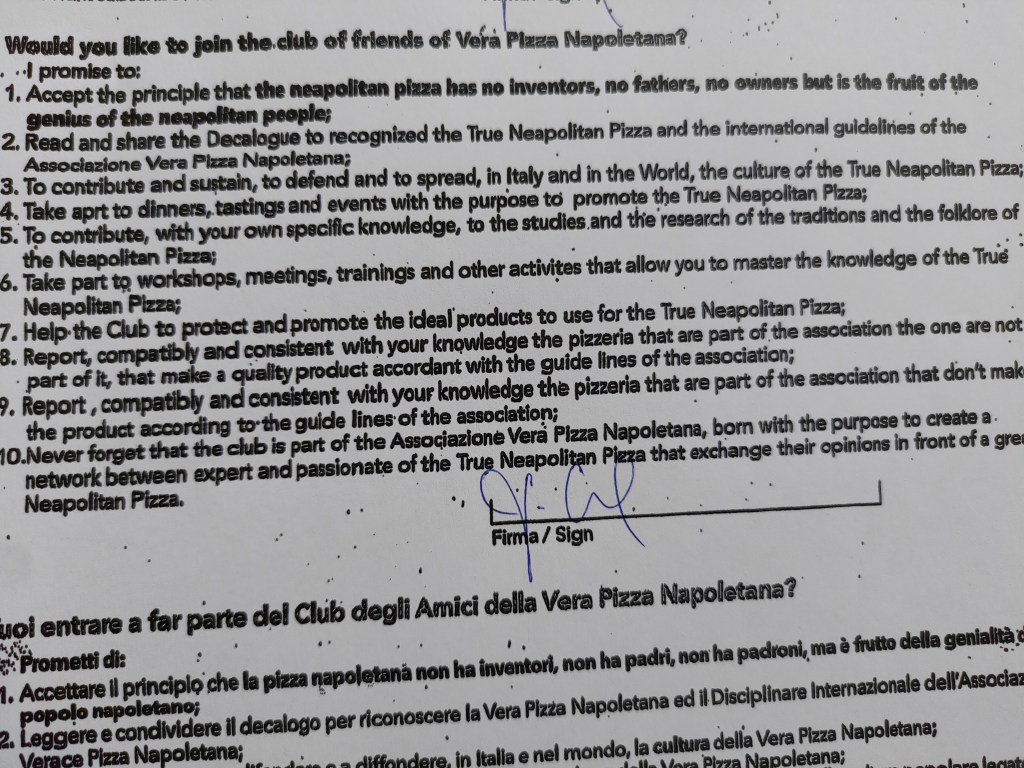

Although arguably a sub-layer of the culinary, pizza napoletana may well be a layer in its own right. The original either comes in its marinara or the margherita variant and has to be produced according to a strict protocol. Dough whose yeast content and resting period is a function of ambient temperature and humidity, an oven heated to between 450°C and 480°C, peeled tomatoes grown on the slopes of Vesuvius, fior di latte cheese with the right amount of moisture, etc. etc. For a modest fee and a written commitment to abide by a charter to preserve Neapolitan tradition, Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana teaches the art to amateur and professional chefs alike. Opinions diverge on how much practice exactly it takes to become proficient at making this delicacy. But everyone agrees that it takes a long time and many pizzas baked. While the primordial origins of pizza napoletana continue to be subject to debate, and probably lie somewhere between pita bread dating back to the ancient Greek layer and Italian farmers spreading dough (an activity referred to as piazzarsi) during a more recent layer, it is now officially credited to the collective genius of the Neapolitan people. Who could argue with that?

La vera pizza napoletana

Signing away life to join the cult

Two unrelated, conspicuously apparent and yet obscure layers concern an architectural feature and a particular social norm. Any visitor will notice the gates to buildings that are at least 2 stories high. Their generous size is as astonishing as the not-so-generous size of the tiny hatches through which pedestrians can squeeze to enter without opening the gate. Upon inquiry, locals explained that these were built before the advent of cars and other motor vehicles to accommodate horses drawing carriages. One can only wonder how tall Neapolitan horses of yesteryear may have been. The other striking sight is the sheer constant, shameless posing by members of the local female population for the purpose of having their pictures taken by what appear to be exclusively male photographers. Inquiries about this habit were answered with its being a custom for 18th birthdays, an explanation that isn’t entirely satisfactory given that the observed age of girls and women engaging in this activity appears to range from anywhere between 8 years and the late 20s.

Tall horses and more 18th birthdays than demographically possible

Transportation is another intriguing layer, especially to a non-Italian visitor. The number of Piaggio two-wheelers and other makes of motorised scooters appears to at least equal, perhaps exceed, the number of human beings encountered in the streets of Napoli. They criss-cross signficantly faster down narrow allies, streets and even staircases than pedestrians and must represent a signifcant cause of morbidity and mortality. Nonetheless, the occasional Fiat Panda also manages to squeeze through.

Piaggio vs. Fiat

Natural disasters resulted in layers that are both geological and temporal in nature. At nearly the same level of the present layer of El D10S, one finds a medival city of curches and artefacts of another monotheistic religion clearly visible to even those visitors who remain on the surface of Napoli. That layer was built upon a Roman layer, which was covered by massive mud slides in the fifth century AD and preserved the market and many adjacent buildings of the ancient Roman city of Neapolis. The erruption of Vesuvius in the first century BC buried and preserved under thick layers of volcanic ash the Roman cities of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Oplontis and Stabiae. A visit to these sites reveals awe-inspiring Roman architecture of public buildings and private dwellings, including the “fishnet” technique of wall construction developed to resist earthquakes, colourful mosaics and well preserved murals that depict the offerings of ancient bath houses and other establishments catering to citizens and travelers. Although the ancient Greeks apparently knew nothing about anti-seismic walls, even deeper underground and further in the past one finds Greek layer that dates back as far as the second millenium BC.

Pompeii and the Roman layer

Visiting Napoli is a voyage through time that is, according to a local student of art history, best remembered by analogy with another culinary highlight: lasagne. Whether the collective genius of the Neapolitan people would agree with being compared to a delicacy from Bologna, the capital of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy, is another question. But it is beyond doubt that Napoli is a complex and multilayered city.

Navigate to

Pages

Categories

Leave a reply to Italy versus Austria: Alto Adige or Südtirol? – My Impressions Cancel reply