Photos by Sebastian Stumpf and Martin

Luckily, someone in the car noticed that we were overshooting the right turn towards Istanbul and that Burgas was, in fact, on the Black Sea coast. This small detour notwithstanding, Turkish passport checks at the Hamzabeyli checkpoint were cleared quickly. Customs were a different story. Instructions by officials were incomprehensible but a closed gate at the final checkpoint and cryptic gestures did suggest that we had to return to the second checkpoint, where we would eventually empty our car and have it x-rayed without all our bags and gear. “Alcohol?”, asked one of the guards while superficially searching our baggage, including the shopping bag filled with supplies and visibly topped with a case of beer and two bottles of schnaps. Sebastian and Martin confidently responded, “no” to reassure the gentleman in performing his duties and gates miraculously opened on our second try.

From the edge of the European Union to the central Anatolian Plateau

As clocks were set forward to local time, a roadside diner just outside of Edirne bid us welcome with delicious Adana Köfte, Lahmacun and Ayran to the Republic of Türkiye, not to be confused with a genus in the kingdom of birds commonly referred to as meleagris gallopavo or wild turkey. A decision had already been made at this point to bypass all monuments and historic treasures of Istanbul lest there wouldn’t be enough time for skiing in on the Anatolian Peninsula. There is no such thing as bypassing Istanbul traffic, however, so despite steering widely clear of the city centre we were given extra time to admire the new Istanbul airport and other awe-inspiring infrastructure built under the aegis of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. That includes the third bridge across the Bosporus, which we crossed into Asia by dusk. Markus admitted to becoming increasingly sympathetic toward the decade-long incumbent of the Turkish presidency, whose policies aren’t unconditionally popular in Turkey or abroad, as the VW Golf made surprisingly fast headway into Anatolia on impeccable six-lane highways. After a short but pleasant overnight stay in Bolu, known to Turkish visitors as the heart of nature, a dinner of Adana Köfte and the first proper Turkish breakfast, we passed Ankara and entered the vast Anatolian Plateau. The endless landscapes had a striking resemblance with the west of the United States, not only because of the massive highways. By mid-afternoon on Wednesday, 8 March, we were greeted by our host at Aladağlar Camping & Bungalows in Çukurbağ.

Aladağlar Camping & Bungalows

Aladağlar

The Aladağlar, or Crimson Mountains, are part of the Anti-Taurus Range that extends northeast of the Taurus Mountains and culminate just south of Kayseri at the summit of Erciyes Dağı, at 3,917m the highest peak in central Anatolia. Aladağlar National Park is home to 3,756m-high Demirkazık Dağı and massive, reddish rock formations that are particularly renowned for climbing. They are also home to Recep İnce, an enthusiastic rock climber from Istanbul not to be confused with the enthusiastic infrastructure builder mentioned above, who left his urban life as a mechanical engineer some 30 years ago to live in Çukurbağ. Since then, he is not only a reliable and warm host to guests from around the world at Aladağlar Camping & Bungalows but also author of the unique and comprehensive Guide to Aladağlar Trekking, Climbing and Ski Touring and has equipped an inestimable number of climbing routes in the crimson rock.

Çukurbağ and sourrdings

As it turned out, to our dismay, Recep’s impressive credentials made the weather forecasts we had consulted no more accurate and the winter of 2023 no colder in the Aladağlar than in the Alps. The last snowfall was weeks in the past and temperatures were far too high for the season. After brief study of the guidebook, a 2015 issue of Ski Rando magazine and some pieces of paper with labels and contour lines (the term map would be misleading) as well as a conversation with Yildirim, a mountain guide from Antalya traveling with a group of French skiers, Emler summit at 3,720m was nonetheless identified as a first objective for Thursday. Harald, who had opted for flight from Sofia to Kayseri instead of the 15-hour drive, soon joined us for dinner in nearby Çamardı, where we were soon overwhelmed by the copious amounts of Pide we had ordered as a side to the Köfte and other meats.

The early morning call for prayer by the local muezzin was ignored as a friend of Recep’s drove us to the snowline above Çukurbağ in his 4×4 Nissan pick-up truck. We skinned up at dawn and soon entered the valley through which the standard route to Emler, clearing the first narrow and steep bit to enter the wider valley above. Confident that the sun would transform the snow to pleasant afternoon corn, the climb was efficient through dramatic landscapes contrasting snow and crimson rock. After a short break on the pass at 3,450m, we reached the summit early afternoon. Warnings in the Ski Rando article would prove right, with the sun having already disappeared behind afternoon clouds and winds picking up. The descent from the summit on sun baked and wind packed crust was nothing short of horrible, but the snow did get a little softer towards the bottom as temperatures rose. Martin complained that, in early March at an altitude of nearly 2,000m we shouldn’t be boarding the 4×4 Nissan and returning to base in disgustingly muddy ski boots. Nevertheless, everyone was happy. We would come to realise only later what a notable success our second day in Türkiye would be.

Emler

After more conversations with Yildirim and the French, the VW Golf effortlessly took us to the end of a dirt road at the northern edge of the mountain range the next day, where we climbed an unknown 3,000m summit in unpleasant, south-westerly winds. Escaping the afternoon clouds, the descent was playful, but snow seemed to be melting at record speeds beneath our feet. That was soon forgotten over afternoon cay with a splendid mountain view in Bademdere.

As the weather forecast was turning, Recep and Yildirim somehow made it sound like a good idea to drive another 100km or so south-west to into the Bolkar Mountains, part of the central Taurus Range. The fastest route “due to traffic conditions” suggested by Google Maps had indeed no traffic but was clearly not the fastest in a vehicle with ground clearance of less than 50cm. Nevertheles, morale remained good after the first U-turn of the day and we arrived at Meydan Yaylası nature preserve, adorned by an abandoned hotel construction project, at 11am to skin up. The second U-turn of the day, 500m below an unknown summit, was significantly more damaging to morale. We nursed the defeat with delicious Köfte, Pide and Ayran at a small cafe in Çiftehan, a nearby village with several thermal spas past their prime. Harald and Martin also sampled the dilapidated hammams. A friendly physical education teacher from Adana encountered in the steam bath clarified that Köfte in Çiftehan was, at best, Turkey’s second best, and that we should really go to Adana to eat Köfte.

Bolkar Mountains

Cappadocia and Kayseri

We decided not to drive to Adana and left the Aladağlar towards Kayseri on Sunday, as warm and gale-force winds moved in from the south. While Adana Köfte remains a staple, Kayseri is mainly known for mantı, small meat dumplings typically served with yoghurt, a cured beef cousin of pastrami called pastırma, and sucuk, a spicy sausage. The latter are on sale in roughly two of three shops across the city. We took full advantage of the local culinary scene and, not least by virtue of Ece’s restaurant suggestions, our focus in Kayseri clearly shifted from mountains to mountains of food. The weather was a factor, too. Really, we just didn’t know yet that we wouldn’t ski for another week.

Johannes, who would substitute for Sarah and Harald, was already waiting for us when we arrived late Sunday afternoon. We checked into bargain but not-so-charming Tower 352 Hotel and went for lunch. Harald, Sebastian and Martin were soon convinced by the offerings of a downtown hammam, housed in a mold-infested historic building, which included the good and, for a few Turkish Liras more, the perfect massage. The choice was an easy one to make. It wasn’t entirely clear what made the perfect massage perfect, but the amount of foam used in the scrub might have been a factor. Martin narrowly escaped suffocation while being scrubbed. While Sebastian concluded that hammams are not his thing, Harald and Martin relished the feeling of superficial cleanliness no less than being wrapped in towels after a final rub. The next few days were spent eating ever more ridiculous quantities for breakfast, lunch and dinner at various local restaurants.

Kayseri

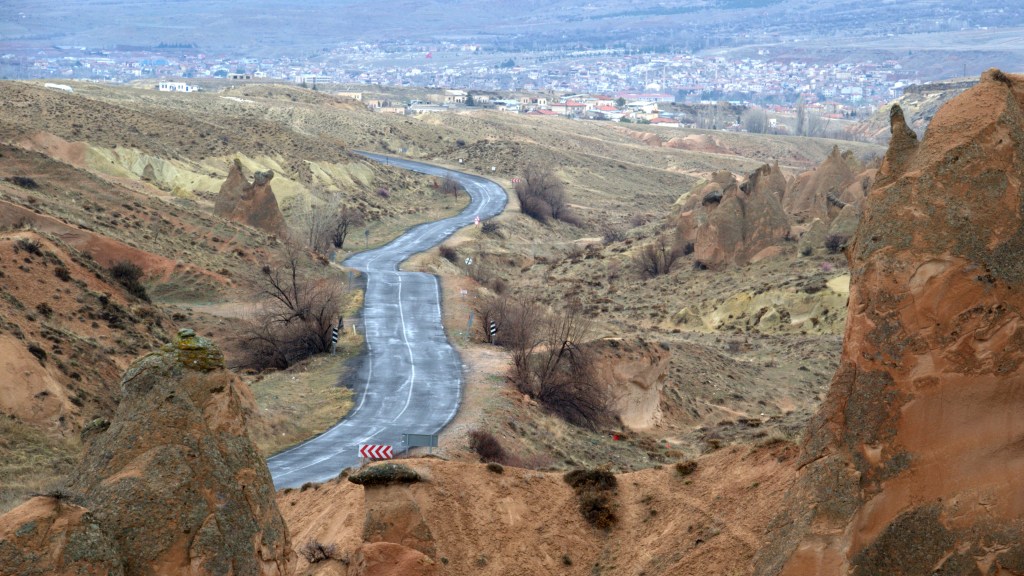

Masses of tourists descend every year onto Göreme, a stone’s throw from Kayseri and one of the top attractions in the Persian Land of Beautiful Horses also known as Cappadocia. The forecast for Monday favoured a visit of the underground cities, while skiing or a the classic hot air balloon ride above the iconic basalt and sandstone formations were off. So while Sarah and Harald caught flights back to Germany, the rest took day trip. We opted for the full monty of tourist activities, except the demonstration of pottery craft, including a visit of imagination valley, fairy chimneys and the Özkonak underground city. Selim, our guide for the day, explained that the more than 200 of these underground structures in Cappadocia were really refuges, where, from the first century AD, locals hid from invaders and persecution for up to one month at the time. A feeling of claustrophobia notwithstanding, the complexity of these manually excavated voids and size of the circular rocks used as rolling doors were impressive.

Göreme and surroundings

As rain got heavier, a hike through one of the valleys was cancelled in favour of, you guessed it, a copious meal at Cancan Restaurant owned by friends of Selim’s. Impressive building and infrastructure remained the focus of the conversation, albeit in the more contemporary context of the upcoming elections. According to Selim, it was far from certain that R.T. Erdoğan and his AKP Party would win another victory despite their achievement, as apparently any Turk would confirm, of building excellent roads throughout the country. Meanwhile our confidence grew that snow was falling at higher altitudes and Selim assured us that he would put in a good word for our skiing ambitions in his prayers.

Unfortunately, Selim’s prayers were not heard and Allah had other plans. Martin seriously toyed with the thought of waiting in the car, or perhaps at Arlberg Café, as we pulled into the parking lot of Erciyes ski resort amid warm winds and fog. Lifts were closed because of the storm and a lack of snow. But somewhere, someone still saw a shimmer of hope that a window of decent weather and visibility would allow for the climb to the summit of Erciyes Dağı. We pulled out our skins next to a group of Mexicans, who looked lost and had trouble carrying their skis. Surely, they were no less disillusioned with skiing than we were. As winds got stronger, visibility worse, and the ice crystals blown into our faces more painful, a prayer room at the top of a chairlift provided welcome shelter for a break and a straightforward decision to abort the mission.

Another U-turn at Erciyes

A last supper in Kayseri was devoured at an excellent restaurant serving Circassian cuisine. Surprised that Köfte was absent from the menu and utterly ignorant of the very existence of the Circassians as an ethnic group, we learned that these people, also referred to as Cherkess or Adyghe, were native to the north Caucasus and had exiled in Turkey in large numbers. The food was as delicious and we overate in the same manner as in other Anatolian or Kayseri eatery. We left Kayseri at dawn on Wednesday morning for an unknown destination further east.

Leave a comment