The scenery through which my southbound bus ride took me, past the Iztaccihuatl and Popocatépetl volcanoes and through the Sierra Madre del Sur, was breathtaking. After my less than successful visit to some of the most renowned cultural sites in CDMX, I tried to redeem myself with an extended stop in the city of Oaxaca, another highlight of Mexican heritage, before heading east towards the Yucatan peninsula.

Oaxaca

I had previously visited only the Pacific coast of the eponymous state. While the first settlements in this area date back to long before the Aztec period, modern-day Oaxaca de Juárez is a tourist attraction mainly because of its colonial architecture and archaeological sites. As nearly all Mexicans I spoke to assured me, and no less a reason for my decision to take this detour, it also boasts a rich cuisine and is considered something like a culinary capital of the country. By the time I was closing in on the city, the list of “must-try” restaurants I had complied from various sources had grown to an impressive length utterly impossible to get through in a few days, even if one were to eat three full meals a day, a task no easier given the ingredients of most Mexican meals. I had also messaged various cooking schools, of which there seemed to be as many as restaurants, to go beyond passive consumption of Oaxacan food on my visit. Surprisingly, none of them seemed to offer classes on any of the days of my stay.

Oaxaca historic centre

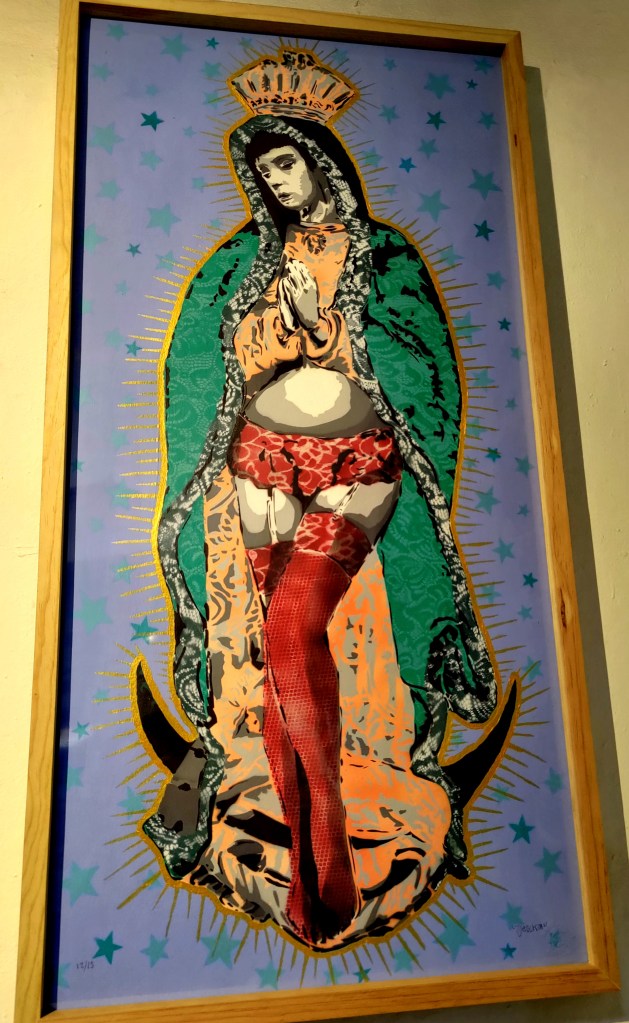

For all its colonial charms and plentiful colours, the historic centre was mainly made up of buildings with a striking resemblance to each other. They usually featured a similar structure and a court yard decorated more or less creatively and which had been, either on its own or with the rest of the building, turned into a hotel or a fancy restaurant catering to tourists. I stayed at Hotel Casona, whose courtyard sported, albeit not entirely without taste, a somewhat questionable Catholic style. Another courtyard of a somewhat different nature was found at the Museum of Oaxacan Cultures that held various artifacts of indigenous cultures that had populated the area from 400 BC until destruction of the last one by Spanish colonialists. Street art on walls and galleries of various contemporary artistic endeavours were a welcome change to the pre- and colonial atmosphere.

Oaxacan art from pre-, peri- and post-colonial times

In the end, I spent most of my time with eating at restaurants randomly drawn from the “must-try” list and sampling through the countless types of artisanal mezcal produced locally. Despite my best efforts and cutting of a few corners, such as by ordering a main that combined two distinct types into one, I did not manage to eat all colours and types of mole that were commonly prepared in Oaxacan restaurants. At 50-plus percent of alcohol content, getting a decently sized sample of different mezcals at any given bar was another task the completion of which would remain a lofty goal.

Coffee, mezcal, other delights and books?

When I had already lost all hope, Gerardo replied to one of my messages and said that he and his mother, Socorro, would be happy to host me at a class in traditional Oaxacan cuisine. Along with two French travellers who were on an extended road trip through Mexico, Gerardo took me to Mercado de Abastos the next day. We procured a long list of ingredients, engaged in small talk with various merchants and marvelled at the sheer endless range of vegetables, fruits, dairy products, spices and ready-made snacks that were on sale at the market for bargain prices. The selection of chilli peppers alone was awe-inspiring. Gerardo, unimpressed, seemed to comment on every product we chose to pick up at the market with the observation that, “it was very popular in the area and that he liked it.” What a lucky man he was.

Mercado de Abastos and Mercado 20 de Noviembre

We then proceeded to having beer and mezcal at Gerardo’s home, half of which he and Socorro had turned into a colourful, outdoor kitchen for cooking classes. We followed Gerardo’s cooking instructions to the dot and prepared a traditional vegetable soup followed by chicken with mole verde and, lest we forget, home made tortillas. As any traveler in Mexico knows, the quantity of tortillas consumed in the country tends to infinity and the number of different types, and different names to call them by, is likely as vast as the United States of Mexico themselves. While the type of flour makes for a straightforward, and usually binary, distinction, more granular types tend to be defined along dimensions of thickness, diameter, baking time and topping. We prepared there different types. My hopes of bringing some of this traditional cooking back to Europe were soon dashed when Gerardo responded to my question of why there were few, dare I say no, traditional Mexican restaurants outside of Mexico with the simple assertion that the right ingredients were only available in Mexico. I decided to bid farewell to mole verde then and there while enjoying our home cooked meal.

Gerardo and Socorro at La Cocina Oaxaqueña cooking school

Yucatan

I arrived in Mérida late at night and checked into Kuka y Naranjo, a tastefully furnished place that calls itself hotelito cultural and takes pride in “promoting Yucatecan culture through sustainable experiences.” It was not entirely clear to me what exactly that meant but I felt right at home, not least because my small room was equipped not only with a comfortable bed but also with a hammock.

Until recently, I would have never even dreamt of taking an all-inclusive guided tour to a region’s main tourist attraction that included not only pick-up service from a nominated hotel but also a strict schedule for the entire day and lunch. Even if I had in fact toyed with such a thought, I would have never publicly admitted to doing so. But times do change and some careful research revealed that the most interesting Yucatecan sites were far apart and not easily reached by public transport. It also seemed plausible that visiting century-old piles of rocks could be more interesting when accompanied by a gifted storyteller. I was thus picked up at 8am the next morning by a minibus filled with other visitors from California, central Mexico and Japan, and Samuel, our guide for the day, after the friendly kitchen staff at Kuka y Naranjo had packed my sustainable breakfast into a glass jar.

Kuka y Naranjo and Mérida

Samuel was of Mayan descent and, as he explained, wanted to Mayan just like anyone who wanted to be a dog or a cat could be, well, a dog or a cat. The analogy remained obscure but it was clear that his desire had something to do with pride in heritage, speaking Mayan language and setting oneself apart from anything and anyone non-Mayan in Yucatan, including the local government, which allegedly used the Mayan label mainly as a marketing ploy to sell overpriced goods and services to tourists. The bus ride was shortened by loud music interpreted by famous Mayan artists, also known outside of Yucatan by their artistic pseudonyms of David Bowie and The Rolling Stones.

On the way to Kabah, the first Mayan site on our schedule for the day, we stopped at one of the several thousands of water-filled caverns and referred to as cenote. Legend has it that, as appears to be the case with many names and terms in colonised lands, the name Yucatan derived from a misinterpretation by newly arrived colonialists of the Mayan phrase for pointing out an absence of understanding and the word cenote from a mispronunciation. I had some doubts about the veracity of this information. Either way, these geological features were impressive. They dated back to collapsing cracks in the ground left by the impact of the infamous meteorite that hit the peninsula more than 60 million years ago. While the ancient Maya populations used them as sources of fresh water to sustain their subsistence, present-day tourists mainly value them for bathing. Turns out that the 200,000 or so square kilometres of land that make up Yucatan are almost completely flat and devoid of rivers, lakes or other kinds of natural sources of water. Why ancient Mayas built their settlements in such a hostile environment is difficult to comprehend. It is less surprising that ensuring a sufficient water supply was a constant and existential preoccupation at the time. Kabah nonetheless developed into a major administrative centre home to some 12,000 inhabitants at its climax around 900 AD, a population nearly matched by the number of well-preserved statues and depictions of Chaac, the long-nosed Mayan rain god. With most cenotes several kilometres away, the citizens of Kabah built cisterns with a bottom layer of ashes to capture and filter water from daily rain. Rain, of course, was daily only in times of benevolence when Chaac could be successfully appeased. As other depictions testify, his more irate phases associated with a lack of rain would frequently lead to social unrest and even war.

No cenote or other sources of water near Kabah

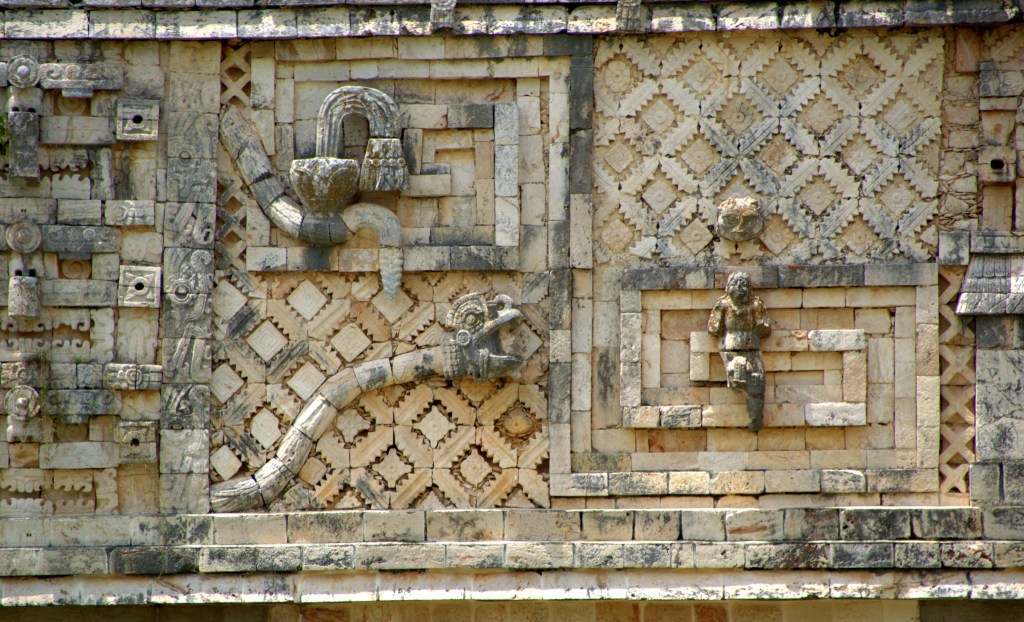

Nearby Uxmal was likely inhabited by an even larger population and served not only for administration but also as a major religious centre. Administrative structures and practices do not appear to have become any simpler between those times and modern-day Mexico, as demonstrated by incomprehensible pricing policies and separate ticket booths to purchase of both, a federal and a state-level ticket, and pass separate federal and state-level turnstiles to access the same archaeological site. Invariably, the price one ends up paying as a visitor from outside of Yucatan at first seems outrageous but subsequently becomes a little more palatable once one gets closer to the grand Pirámide del adivino and its door through which Mayan kings would walk to speak to the gods. The pyramid was built by a dwarf in only one night, or so the tale goes. Uxmal’s main square, on the other hand, had surely been constructed by ingenious architects who skilfully combined walls to improve acoustics, buildings oriented according to constellations in the night sky, columns in each corner that would support the unearthly weight of heaven above, and, most notably, 13 doors to access the 13 levels of that same heaven as well as nine underground rooms to access all levels of the underworld. Life most have been a complex affair with all these levels of existence to choose from or be thrown into. Exploitation of labourers and outright slavery to build venues for ballgames were Mayan traditions that have been successfully preserved until 2022. With some resemblance to contemporary tradition, the Mayan beautiful game was likely also played with a ball, pitted two teams against each other and allowed players to gain social prestige. Contrary to modern practice, however, it was a divinatory ritual set in the underworld. As Samuel pointed out, this is about as much as is known about its intricacies and tales about how scores were kept, the fate of the losing side or human sacrifice should not be taken at face value.

Uxmal

After visits to the local chocolate museum, the historic centre of Mérida and the traditional La Bierhaus, I soon boarded an eastbound bus that would take me to Cancún. The strategy of keeping my stay short to avoid all gringo tourists vacationing on the Caribbean coast was a success but I failed miserably at saving a buck by finding a hotel close to the airport, leaving me at mercy of the Cancún airport taxi cartel that charges extortionate sums for short rides. Nevertheless and several hundred pesos in cab rides later, I managed to catch an early morning flight to leave Mexico bound for Cuba.

Leave a comment